Dedication

To the working-class backbone who lived the collapse.

To the people who refused to quit, even after the system turned on them.

To the younger generation—those who left, those who stayed, and all who were shaped by what happened here.

To the builder, the chronicler, the one carrying the burden forward when others walked away.

And to my family and friends—many gone but never forgotten.

Author’s Note

This book is not a full chronicle of the Foothills Corridor’s past, nor a sweeping declaration of its future. It is something more focused—and more urgent.

It is a seed.

The structure of this book is intentional. The Parts are the major chapters—the large movements of history and possibility. The individual Chapters within each Part are meant to be tactical essays, each designed to strike directly at a core reality without drifting into unnecessary elaboration. They are precise by design, anchored by subheaders to guide the reader through a dense, complex subject without losing momentum.

This is not a novel. It is not a complete compendium. It is a cornerstone—the beginning of a larger architecture.

Each chapter was crafted not to exhaust the subject, but to position it. To reveal how we got here, to highlight what was lost, and to propose the first steps forward. The full story of the Foothills Corridor’s future has yet to be written. This book is not that ending. It is the catalyst for a conversation, a call to action, and an open hand to those who believe our best chapters are still ahead.

If this work takes root, future volumes will deepen and expand these foundations. If it fails, let it at least stand as a marker of what was seen clearly and said without apology.

Either way, the work begins here.

— James Thomas Shell

PART I

THE COLLAPSE

How a Region Built on Work Was Brought to Its Knees

Before we can talk about rebuilding the Foothills Corridor, we have to face how it fell apart.

For much of the 20th century, the Foothills were a vital contributor to America’s industrial economy. We built furniture that furnished homes nationwide, produced textiles that clothed generations, and developed fiber optics that advanced global communications. We didn’t ask for handouts. We worked hard.

But starting in the 1980s, the rules changed. Washington signed deals. Wall Street chased margins. Companies followed cheap labor. And just like that, our factories became fossils. Automation replaced muscle. Globalization erased whole towns from the economic map. And while the rest of the country moved on, we were told to "adapt"—as if resilience alone could replace 40,000 lost jobs.

This chapter is not a eulogy. It’s a reckoning. We’re going to examine the forces that gutted our communities—free trade, policy failure, political neglect, and a culture that prioritized urban growth while rural places were allowed to rot. We’re going to look at what happens when you rip out the economic heart of a region without offering anything to replace it. And we’re going to hear from the people who lived it—not just economists or politicians, but the working-class backbone of this corridor: machinists, nurses, line workers, teachers, and sons and daughters who watched everything change.

To understand where we’re going, we have to remember how we got here. This is the story of the collapse. Not to wallow in it—but to learn from it, honor the pain, and make damn sure we don’t repeat it.

Chapter 1

A Manufacturing Powerhouse Eclipsed

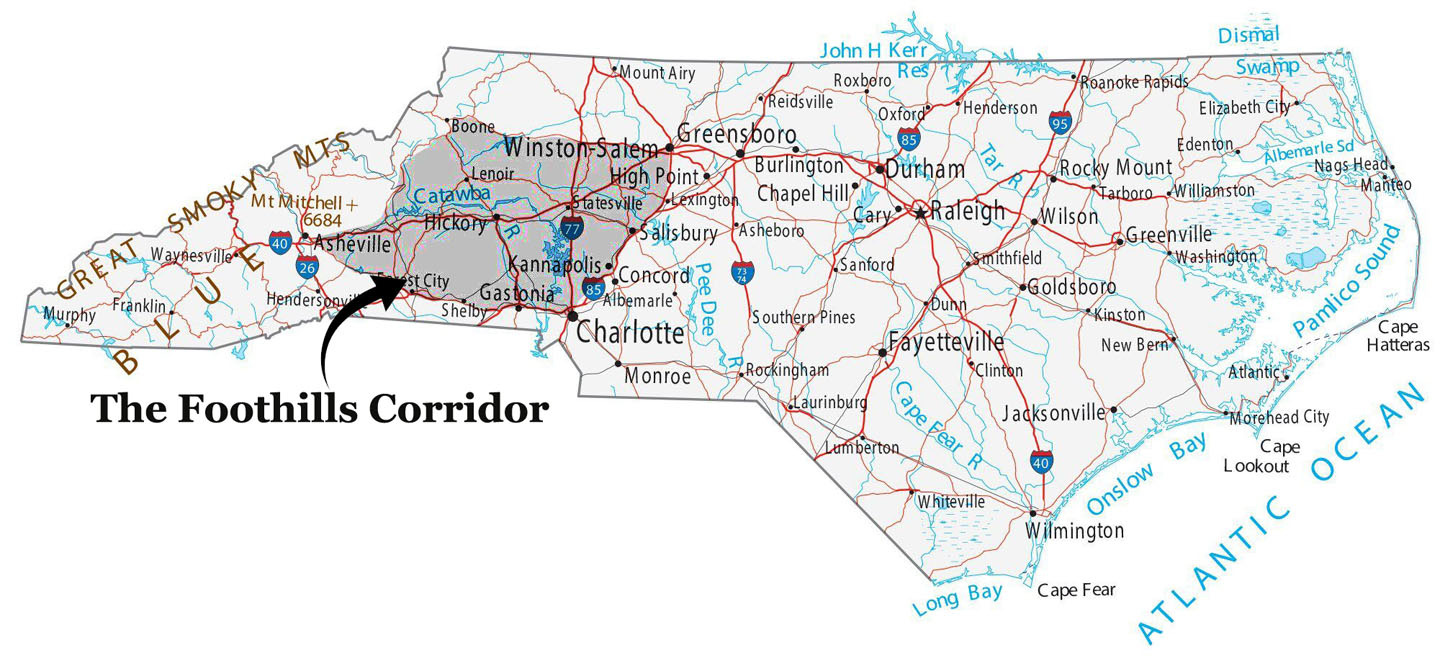

For much of the 20th century, the Foothills Corridor was a crucible of American industry. This 20-county stretch of western North Carolina, anchored by cities like Hickory, Morganton, Lenoir, Statesville, Winston-Salem, North Wilkesboro, Gastonia, and Marion, didn’t just ride the manufacturing wave—it helped define it. If you grew up here, someone in your family likely worked in furniture, textiles, hosiery, fiber optics, or millwork. You didn’t have to leave town to find a living wage. You could build a life with your hands, your back, and your grit.

By the 1950s and 60s, the region had achieved near-mythic status in certain sectors. Hickory became synonymous with high-quality furniture. Morganton and Valdese were known for textiles and hosiery. Claremont churned out fiber optics and cable. Winston-Salem stood tall as a twin pillar of tobacco and textiles. North Wilkesboro was home to Holly Farms and deep roots in furniture and tool manufacturing. Gastonia thrived with a massive textile base that once defined its civic and economic identity. Marion supported sprawling mills and a working-class community rooted in industrial rhythm. There was pride in the precision, endurance, and craftsmanship that defined the region’s workforce. These weren’t just jobs—they were generational vocations. Kids grew up expecting to follow their parents into the mills or onto the factory floor. The economy was local, and so was the loyalty.

The identity of the Foothills wasn’t just rooted in what people produced—it was woven into how they lived. It was a culture built around craftsmanship, mutual reliance, and a quiet pride that didn't need headlines or handouts. Families took pride in doing things the right way, not the fast way. Communities celebrated endurance over flash, and dignity over wealth. To be from the Foothills was to belong to something steady, tangible, and fiercely self-sufficient—a cultural spine that remained intact even as economic pressures mounted.

In those days, the rhythm of life matched the rhythm of production. Whistles blew at shift change. Workers packed local diners and cafes. Churches, ballfields, and civic clubs were filled with people whose lives were tethered to industrial schedules. It was a social contract—if you showed up and worked hard, the community took care of you. Paychecks turned into mortgages, company benefits turned into pensions, and a high school diploma was often enough to secure a middle-class future.

But underneath the surface of prosperity, the tectonic plates were shifting. Even before NAFTA, local giants like Broyhill and Henredon had begun shedding jobs—quiet warnings that the era of steady industrial growth was ending.”

This illustration contrasts the vibrant, working-class identity of the 20th century with the economic dislocation and civic hollowing that followed.

The Globalization Tsunami

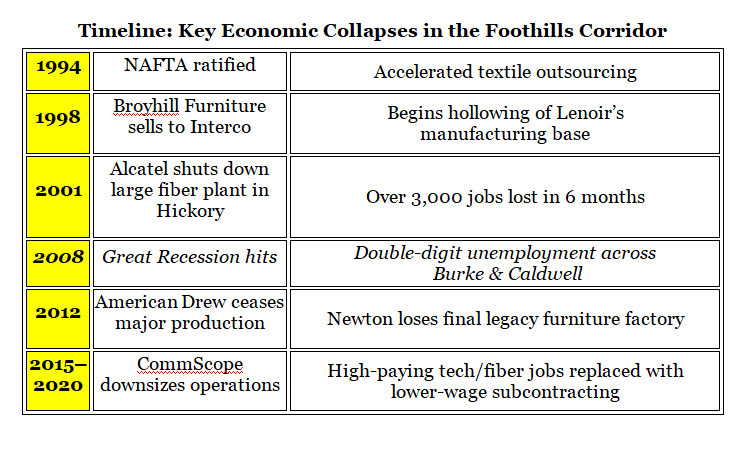

The first tremors were subtle. Companies began to flirt with overseas suppliers. Executives quietly explored "cost efficiencies." By the late 1980s, whispers of layoffs turned into headlines. When NAFTA passed in 1994, the exodus accelerated. Suddenly, whole operations were uprooted. Mills that had run for generations were shuttered overnight. Plants were dismantled and shipped overseas—sometimes literally, with machinery packed into crates bound for China, Mexico, or Vietnam.

NAFTA had been sold as a win-win: North American unity, consumer choice, and job growth. But on the ground in Hickory, Gastonia, North Wilkesboro, Marion, and Lenoir, what it meant was plant closures, auction signs, and men in their 50s sitting in job training centers wondering what went wrong. It meant second mortgages, strained marriages, and children who learned to do without. It meant that being born into a hardworking family no longer guaranteed stability—it just guaranteed pain when the rug got pulled out.

In Hickory alone, tens of thousands of jobs vanished over the next two decades. Caldwell County, once booming with furniture factories, saw its industrial tax base crumble. The decline wasn’t just economic—it was cultural. A way of life was collapsing in slow motion. And the worst part? No one in Washington seemed to care.

North Wilkesboro lost Holly Farms, a major employer and cultural anchor in the region. Gastonia, once a textile titan, watched its mills go dark and its downtown hollow out. In towns like Marion, where mill whistles once dictated the flow of life, silence settled in their place.

The irony is that the workers in the Foothills didn’t fail their industries—the industries failed them. These were not people resisting change. They were people betrayed by a system that commodified their livelihoods. The same government that once promoted the American industrial worker now incentivized their obsolescence. And when the factories closed, there were no safety nets, no retraining programs with real bite—just platitudes and finger-pointing.

The Collapse by Numbers

The data from the 1990s and early 2000s is staggering:

· Over 40,000 manufacturing jobs lost in the Hickory metro area between 1990 and 2010.

· Dozens of plant closures across Burke, Caldwell, and Catawba Counties alone.

· Unemployment rates in some towns spiking above 15%.

· Poverty rates doubling in certain rural areas.

The psychological toll was harder to quantify but just as real. Generational trauma set in. A once-proud workforce was labeled as “unskilled” or “left behind.” Substance abuse climbed. So did divorce, depression, and displacement. Small towns that had once thrived on industrial tax revenue struggled to keep schools open and roads maintained.

And the young people? They left.

The Hollowing Out

With few jobs and no clear path forward, a generation of talent drained out of the Corridor. The brain drain wasn’t just academic—it was emotional. Kids who once might’ve taken over the family trade now chased jobs in Charlotte, Raleigh, or out of state entirely. The result was a demographic gut punch: aging populations, declining school enrollment, and a shrinking civic core.

Local businesses that depended on factory traffic—diners, hardware stores, even barbershops—saw their customer bases evaporate. Community institutions began to fray. Church attendance waned. Volunteer fire departments aged out. In many places, the only growing sector was despair.

But this wasn’t failure. This was fallout.

The manufacturing powerhouse that once defined the Foothills didn’t collapse because it was weak. It collapsed because it was targeted—by trade policies, corporate greed, and political neglect. The region’s loyalty to labor was not repaid with loyalty from leadership. Instead, it was met with indifference or condescension.

Lessons Buried in the Rubble

If there’s one thing we should learn from this collapse, it’s this: the decline wasn’t inevitable. It was the result of decisions—made in boardrooms and policy circles—that treated places like the Foothills Corridor as expendable. We weren’t too slow to adapt. We were deliberately left behind.

And yet, even as the factories closed and the paychecks dried up, something else lingered—a stubborn will to survive. Families leaned on each other. Faith communities rallied. Local leaders scraped together grants, partnerships, and hope. The region never lost its grit. It only lost its platform.

Today, that platform is being rebuilt—but not on the old model. The days of massive single-employer towns may be over. But the spirit of craftsmanship, discipline, and local pride hasn’t gone anywhere. In fact, it may be the very thing that saves us.

If this matters…

Comment. Send a letter you'd like me to post. Like the Hound”s Signal and share my my various platforms. Subscribe. Share it on your personal platforms. Share your ideas with me. Tell me where you think I am wrong. If you'd like to comment, but don't want your comments publicized, then they won't be. I am here to engage you.